Jot is a library for persisting and applying .NET application state.

Jot - a .NET library for state persistence

Introduction

Almost every application needs to keep track of its own state, regardless of what it otherwise does. This typically includes:

- Sizes and locations of movable/resizable elements of the UI (forms, tool windows, draggable toolbars…)

- Last entered data (e.g. username, selected tab indexes, recently opened files…)

- Settings and user preferences

A common approach is to store this data in a .settings file and read and update it as needed. This involves writing a lot of boilerplate code to copy that data back and forth. This code is generally tedious, error-prone and no fun to write.

With Jot, you only need to declare which properties of which objects you want to track, and when to persist and apply data. This is a better abstraction for this requirement, resulting in more readable and concise code.

Installation

Jot is available on NuGet and can be installed from the package manager console:

install-package Jot

Example: Persisting the size and location of a Window

To illustrate the basic idea, let’s compare two ways of dealing with this requirement: .settings file (Scenario A) versus Jot (Scenario B).

Scenario A (.settings file)

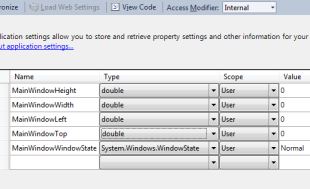

Step 1: Define settings

Step 2: Apply previously stored data

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

this.Left = MySettings.Default.MainWindowLeft;

this.Top = MySettings.Default.MainWindowTop;

this.Width = MySettings.Default.MainWindowWidth;

this.Height = MySettings.Default.MainWindowHeight;

this.WindowState = MySettings.Default.MainWindowWindowState;

}

Step 3: Persist updated data before the window is closed

protected override void OnClosed(EventArgs e)

{

MySettings.Default.MainWindowLeft = this.Left;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowTop = this.Top;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowWidth = this.Width;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowHeight = this.Height;

MySettings.Default.MainWindowWindowState = this.WindowState;

MySettings.Default.Save();

base.OnClosed(e);

}

This is a lot of work, even for a single window. If there were 10 resizable/movable elements of the UI, the settings file would become a jungle of similarly named properties, making this code quite tedious and error prone to write.

Also notice that for each property of the window, we need to mention it in five places (in the settings file, twice in the constructor and twice in OnClosed).

Scenario B (Jot)

Step 1: Create and configure the tracker

// Expose services as static class to keep the example simple

static class Services

{

// expose the tracker instance

public static Tracker Tracker = new Tracker();

static Services()

{

// tell Jot how to track Window objects

Tracker.Configure<Window>()

.Id(w => w.Name)

.Properties(w => new { w.Height, w.Width, w.Left, w.Top, w.WindowState })

.PersistOn(nameof(Window.WindowClosed))

}

}

Step 2: Track the window instance

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

// Start tracking the Window instance.

// This will apply any previously stored data and start listening for "WindowClosed" event to persist new data.

Services.Tracker.Track(this);

}

That’s it. We’ve set up tracking for all window objects in one place, so that all we need to to is call tracker.Track(window) on each window instance to preserve it’s size and location. It’s concise, the intent is clear, and there’s no repetition. Notice also that we’ve mentioned each property only once, and it would be trivial to track additional properties.

Real world form/window tracking

The above code (both scenarios) works but it doesn’t account for a few things. The first one is multiple displays. Screens can be unplugged, and we never want to position a window onto a screen that’s no longer there. We can get around this problem very easily if we make the screen resolution part of the identifier. Jot will then track the same window separately for each screen configuration.

WPF Window

Here’s how to properly track a WPF window:

// 1. tell the tracker how to track Window objects (this goes in a startup class)

tracker.Configure<Window>()

.Id(w => w.Name, SystemInformation.VirtualScreen.Size) // <-- include the screen resolution in the id

.Properties(w => new { w.Top, w.Width, w.Height, w.Left, w.WindowState })

.PersistOn(nameof(Window.Closing))

.StopTrackingOn(nameof(Window.Closing));

// 2. in the Window constructor

public Window1()

{

// fetch the tracker instance e.g. via IOC or static property

var tracker = Services.Tracker;

tracker.Track(this);

}

The Id method has a params object [] parameter that can be used to define a namespace for the id. These parameters simply get ToString-ed and concatenated to the Id. By using the screen resolution as the namespace, we ensure that we maintain separate configurations for different resolutions.

Windows forms

Winforms have a few additional caveats:

- Forms will return bogus size/location data for maximized/minimized forms, so we have to cancel persisting those

- Tracking needs to be applied during

OnLoadsinceTopandLeftproperties set in the constructor are ignored

Here’s how to properly track (Windows) Forms:

// tell the tracker how to track Form objects (this goes in a startup class)

tracker.Configure<Form>()

.Id(f => f.Name, SystemInformation.VirtualScreen.Size) // <-- include the screen resolution in the id

.Properties(f => new { f.Top, f.Width, f.Height, f.Left, f.WindowState })

.PersistOn(nameof(Form.Move), nameof(Form.Resize), nameof(Form.FormClosing))

.WhenPersistingProperty((f, p) => p.Cancel = (f.WindowState != FormWindowState.Normal && (p.Property == nameof(Form.Height) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Width) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Top) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Left)))) // do not track form size and location when minimized/maximized

.StopTrackingOn(nameof(Form.FormClosing)); // <-- a form should not be persisted after it is closed since properties will be empty

// in the form code

protected override void OnLoad(EventArgs e)

{

// fetch the tracker instance e.g. via IOC or static property

var tracker = Services.Tracker;

tracker.Track(this);

}

Avalonia UI

For Avalonia UI it is similar to WPF with some diferences:

- The screen information is available from the Window class instead of being static.

- Closing the app while being minimized would open the app next time also minimized if we don’t check for that during window load.

- When the app is minimized it reports a negative position instead of the position it would have if not minimized,

so we need to check for negative position values during window load to prevent setting the window out of reach.

// in the Program.cs

public static Tracker Tracker = new Tracker();

// in the Window constructor

public MainWindow()

{

InitializeComponent();

#if DEBUG

this.AttachDevTools();

#endif

var initialPosition = this.Position;

var trackerNamespace = string.Join("_", Screens.All.Select(s => s.WorkingArea.Size.ToString()));

trackerNamespace += "__" + Environment.ProcessPath?.Replace("/", "_").Replace("\\", "_"); // <-- Add this if you want multiple copies of the same app to have different configurations.

Program.Tracker.Configure<Window>()

.Id(w => w.Name, trackerNamespace)

.Properties(w => new { w.WindowState, w.Position, w.Width, w.Height })

.PersistOn(nameof(Window.Closing))

.StopTrackingOn(nameof(Window.Closing));

Program.Tracker.Track(this);

if (this.WindowState == WindowState.Minimized)

{

this.WindowState = WindowState.Normal;

}

if (this.Position.X < -1 || this.Position.Y < -1) // -1 is used by Windows11 when docking windows on the side.

{

this.Position = initialPosition;

}

}

Which properties to track

There are two methods (and several overloads) for telling Jot which properties of a given type to track.

The Properties method accepts an expression that projects the target properties as an anonymous object:

tracker.Configure<Person>()

.Properties(p => new

{

p.Name,

p.LastName,

MothersMaidenName = p.Mother.LastName // <-- can navigate object graph

})

The Property method is used to add propreties one by one. It allows specifying a name and a default value for each property. Since the property name can be passed as a string, this overload is useful for situations where the properties to track are determined at runtime.

tracker.Configure<Person>()

.Property(p => p.Name)

.Property(p => p.LastName)

.Property(p => p.Age, -1) // if there's no value in the store, -1 will be set

.Property(p => p.Mother.LastName, "MothersMaidenName") // <-- a name must be provided so it does not colide with p.LastName

The expressions you provide to these methods are used to specify which properties to track. The properties usually belong to the target object itself but they can also navigate through other objects (e.g. p.Mother.LastName). Based on these expressions, Jot will dynamically generate getter and setter methods for reading and writing the data. Both methods (Properties and Property) are cumulative: they add properties to track, rather than overwrite previous calls.

When is the data persisted?

Jot needs to know when a target’s data has changed so it can save the updated data to the store. You can tell Jot to automatically persist a target whenever it (the target) fires an event:

tracker.Configure<Foo>()

.Properties(...)

.PersistOn(nameof(Foo.SomeEvent)) <-- the event that should trigger persisting

You can optionally specify another object as the source of the event:

PersistOn("SomeEvent", otherObject)

You can also explicitly tell Jot to persist a target using the Persist method:

tracker.Persist(targetObj);

To tell Jot to persist all tracked objects, use the PersistAll method:

tracker.PersistAll();

Usually, this would be during an application shutdown or at the end of a web request. Jot maintains a list of weak references to target objects. Targets that are already garbage collected are ignored.

Some objects survive until the end of the application without being in a usable state. For example, a disposed form can still be referenced (and thus not garbage collected). We do not want to continue tracking that form after it is disposed because it will have bogus property values which we do not want to save to the store. For such cases, we can tell Jot to stop tracking a particular object by calling StopTracking:

tracker.StopTracking(targetObj);

We can also tell Jot to automatically stop tracking an object when it raises a certain event:

tracker.Configure<Form>()

.Properties(...)

.PersistOn(...)

.StopTrackingOn(nameof(Form.Closed)) <-- the event that should cause the tracker to stop tracking the target

Where is the data stored?

The Tracker class constructor has an optional parameter that allows you to specify where the data will be stored.

Tracker(IStore store)

Jot comes with a built-in implementation of IStore called JsonFileStore. If the IStore argument is not provided, the data will be stored in json files in the following folder: %AppData%\[company name]\[application name]. The company name and application name are read from the entry assembly’s attributes). For each target object, there will be a separate file. Data is stored in separate files in order to make reading and writing data fast.

To keep using the JSON file store, but store the data in a per-machine folder (e.g. CommonApplicationData), configure the tracker like so:

var tracker = new Tracker(new JsonFileStore(Environment.SpecialFolder.CommonApplicationData));

Or specify the storage folder explicitly:

var tracker = new Tracker(new JsonFileStore(@"c:\example\path\"));

Here’s what the stored data looks like:

Custom storage

The IStore interface is very simple. For a given Id, it needs to be able to store and retrieve a dictionary of values.

public interface IStore

{

void SetData(string id, IDictionary<string, object> values);

IDictionary<string, object> GetData(string id);

}

You can use this interface to make Jot store data anywhere you like e.g. in the cloud (to share settings for a user between machines) or a database.

Value conversions and cancellation

Jot lets you hook into the Apply and Persist operations. You can use this to perform value conversion and cancel persisting or applying data. As we’ve seen in the WinForms example, we can cancel applying size/location properties for Forms that are maximized or minimized:

tracker.Configure<Form>()

.Id(...)

.Properties(...)

.WhenPersistingProperty((f, p) => p.Cancel = (f.WindowState != FormWindowState.Normal && (p.Property == nameof(Form.Height) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Width) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Top) || p.Property == nameof(Form.Left))))

There are four hooks you can use: WhenPersistingProperty, WhenApplyingProperty, WhenAppliedState and WhenPersisted.

Tracking and inheritance

Tracking is configured per-type, meaning that a separate TrackingConfiguration<T> object will need to be defined for each type of object we track. This configuration object tells Jot how to track objects of that type, but it also applies to objects of derived types.

When configuring tracking for a derived type, Jot will examine the inheritance hierarchy of that type and look for the closest ancestor type for which a tracking configuration already exists. If it finds one, it will first create a copy of the base type’s tracking configuration which you can then further customize.

For example, let’s suppose you define a class called MyForm that derives from Form. In addition to tracking the size and location, you also want to track the selected tab of a TabControl that’s part of MyForm. Here’s what that might look like:

// configure tracking for Form

tracker.Configure<Form>()

.Id(f => f.Name, SystemInformation.VirtualScreen.Size)

.Properties(f => new { f.Height, f.Width, f.Left, f.Top, f.WindowState})

.PersistOn(nameof(Form.Closing))

.StopTrackingOn(nameof(Form.Closed))

.WhenPersistingProperty((f, p) => p.Cancel = (f.WindowState != FormWindowState.Normal && p.Property != nameof(Form.WindowState)))

// add the selected tab index for MyForm (everything else is already copied from the configuration for Form)

tracker.Configure<MyForm>()

.Properties(f => f.tabControl1.SelectedIndex);

We do not have to repeat the tracking configuration for size and location. Since MyForm derives from Form, the configuration for MyForm will be copied from the configuration for Form and we only need to add the additional f.tabControl1.SelectedTabIndex property.

Furthermore, if we configure tracking for Form but not for MyForm, Jot will track MyForm instances using the tracking configuration for Form.

The ITrackingAware interface

Sometimes we cannot know at compile time which properties to track. In those situations, we need to configure tracking on a per-instance basis at runtime. To do this, our tracked objects can implement the ITrackingAware interface.

public interface ITrackingAware<T>

{

void ConfigureTracking(TrackingConfiguration<T> configuration);

}

In the ConfigureTracking method, the object can dynamically specify which properties to track. The configuration parameter is specific to that instance (and not the type) so each instance can independently adjust its tracking configuration.

For example, let’s assume we have a form that has a datagrid, and we want to track the widths of grid columns. We could track each grid column object as a separate object, but we can also track those columns as part of tracking the form. Here’s what that might look like:

public class MyFormWithDataGrid : ITrackingAware

{

protected override void OnLoad(EventArgs e)

{

Services.Tracker.Track(this);

}

public void InitConfiguration(TrackingConfiguration configuration)

{

// include data grid column widths when tracking this form

for (int i = 0; i < dataGridView1.Columns.Count; i++)

{

var idx = i; // capture i into a variable (cannot use i directly since it changes in each iteration)

configuration.Property("grid_c_" + dataGridView1.Columns[idx].Name, f => f.dataGridView1.Columns[idx].Width);

}

}

}

IOC integration

Once we’ve explained to Jot how to track different types of objects, all that’s needed in order for Jot to track instances of those types is to call:

tracker.Track(obj);

Here’s the really cool part… When using an IOC container, many objects in the application will be created by the container. This gives us an opportunity to automatically track all created objects by hooking into the container.

For example, with SimpleInjector we can do this quite easily, with a single line of code:

var tracker = new Jot.Tracker();

var container = new SimpleInjector.Container();

//configure tracking and apply previously stored data to all created objects

container.RegisterInitializer(d => { tracker.Track(d.Instance); }, cx => true);

With this in place, we can easily make any property of any object persistent, just by modifying the tracking configuration for its type. Neat!

Demos

Demo projects for WPF and WinForms are included in the repository.

Contributing

You can contribute to this project in the usual way:

- First of all, don’t forget to star the project

- Fork the project

- Push your commits to your fork

- Make a pull request

TODO

- Async support

- IOC demos

- aspnet core (demo + readme section)

- readme topics: unity ioc integration, attribute based configuration